Part I - CASE STUDY 1.1 - Globalisation and tourism in Guilin, China's urban landscape

|

Mainland China had a lot of catching up to do when Deng Xiaoping first announced the Four Modernizations campaign in 1978. The country was amongst the poorest in the world, with a built infrastructure that had changed little since the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) came to power in 1949. The socialist approach to city planning was to focus on industrial development - to create cities of production under the socialist planning principle of 'production first, living conditions later' (xian shengchan, hou shenghuo). Industrial soot and meager housing conditions were the norm for city life throughout China. Deng's Four Modernizations (industry, agriculture, defense, and science and technology) led to a refocusing of industrial production, moving away from an emphasis on heavy machinery and toward an emphasis on consumer products in the 1980s. In China's cities, this was seen in the movement of heavy industry out of the city cores to the periphery, creating new opportunities to create a consumption-driven urban landscape. By the end of the 1990s, most of China's large urban centers were transformed from industrial cities of production to cities of tertiary cities of services and consumption, with landscapes comparable to the China that we recognize today.

|

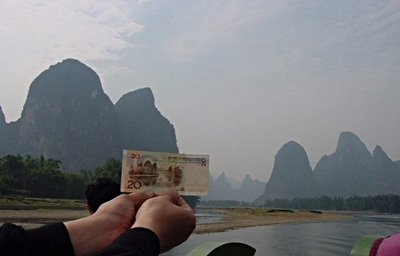

Guilin provides a case study example of the transformation of China's urban landscapes. Guilin is located in Guangxi Province in China's southwest and has long been famed for its setting among towering limestone peaks surrounded by rice paddy fields and flowing rivers. It is one of the major inspirations for traditional Chinese landscape art and calligraphy and an image of the Lijiang (Li River) even appears on China's RMB 20 yuan currency note. However, as with the rest of China, except for Beijing, it entered the 1980s as a dark, gray and soot covered city where tourists primarily stayed waiting to board boats Lijiang cruise boats.

The most significant transformation of the urban landscape of Guilin occurred in the 1990s with the movement of factories out of the city and the cleaning of building facades, especially in the older central commercial areas. A major urban renewal project razed a large part of the city core to create an open plaza with an underground shopping center and a European themed pedestrian retail area (complete with a Dutch windmill on one building façade). The plaza was connected by a broad shopping street to the new downtown, which was also a result of urban renewal. |

|

The plaza area, with its numerous street vendors, had become the center for evening entertainment and recreation activities for both tourists and residents. It was flanked on one side with two massive video screens and the Lijiang (Li River) Waterfall Hotel. The façade of this luxury hotel boasts the largest man-made waterfall in the world, at 45 meters tall and 75 meters wide. Water flows from the top of the hotel each evening for 15 minutes, pulsating to accompanying music. Local residents liken it to a "Las Vegas" style of public theming and display. The hotel has been an iconic part of the Guilin tourism landscape since it opened in 2002.

As impressive as that sight might be, at least when it is flowing to music, an even more dramatic and indelible impact on the Guilin city landscapes has been the creation of the "Two Rivers and Four Lakes" project. Initiated 1998, this project connects the Li River with one of its tributaries and four oxbow lakes (former pathways of the Li River) to create a waterway for boats to take tourists and recreationists around the city. Building the connections among the lakes and rivers was a major urban renewal effort, involving the razing of factories and residences, the clearing of clogged drainage systems, and the building of new water channels. |

At the grand opening of the Two Rivers and Four Lakes project in 2002, the local leader of the CCP, the most powerful political figure in Guilin, proudly proclaimed that if he had listened to the people of Guilin, this "magnificent" project would never have been built. The CCP leader sent government officials overseas to get ideas on how to use this project to beautify the city and turn it into a recreational tourist mecca. It appears that they received their strongest inspiration from the Disney Company's Epcot Center, which is a type of permanent world's fair or world expo in Orlando, Florida. This is seen in the theming of all of the bridges that cross the project's water ways, including a mini-Golden Gate Bridge, a French Arch de Triumph bridge, a Japanese bridge, and an Italian Renaissance bridge, along with traditional Chinese bridges and a "Glass Bridge" that is actually made of a hard, clear plastic, among others. In addition, the banks of the waterway are lined with gardens and architecture that represent different cultural traditions, including a Korean garden, Indonesian buildings, and elaborate Chinese gardens.

|

|

Guilin demonstrates how, by the early 2000s, China's urban consumers were increasingly dreaming and living an international lifestyle defined by a wide variety of consumer goods, global brand names, ubiquitous cell phones, Internet access, fast foods and other convenience foods, and increasingly postmodern public architecture and open spaces. Driven by this, domestic tourism in China expanded year by year through the 1990s, reaching 740 million in 2000, while outbound tourism reached 10.5 million in that same year. Thus, in only two decades, the Chinese economy has evolved from a pre-consumer society (in the Mao Zedong era) to a post-modern or even hyper-modern consumer one.

As with other global cities, the urban built environment in China reflects the place promotional competition that has become so heated among cities as they image themselves as modern and attractive environments for economic investment. In China, urban quality of life has become an economic development tool and a real estate marketing tool that is creating international-class "shoppertainment" and "eatertainment" venues. New China has caught up with, and in some ways surpassed, New Asia. |

This has not come without serious downsides, including a lack of adequate consultation with citizens, which often results in their disempowerment, and the unreflexsive destruction of historical resources, include the traditional urban fabric of many cities. A comparable development environment existed in the US in the first half of the 1900s, but came to a close in the early 1960s following large scale public protests over the negative impacts of urban renewal. Signs are that similar shift in attitude towards development impacts may be taking place in China, today.

Globalization has Disneyfied the Guilin urban landscape (Ritzer & Liska, 1997). This is, apparently, what mass tourists want: it feeds their postmodern addiction to simulcra, fantasy and the superficial. Through the appropriation of images and themes from other places, many modern Chinese cities (or parts of these cities) have engendered a commodified placeless quality that undermines their sense of humanness and community. Such, however, is the price of hyper-modernity. Reference Ritzer, George and Lisak, Allan (1997) 'McDisneyization' and 'Post-Tourism': Complementary perspectices on contemporary tourism. In C. Rojek and J. Urry, eds., Tourism Cultures, pp. 96-109. London: Routledge. photos by Alan A. Lew |