PART II - CASE STUDY 2.2

Community-based conservation in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa

Community-based conservation in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa

|

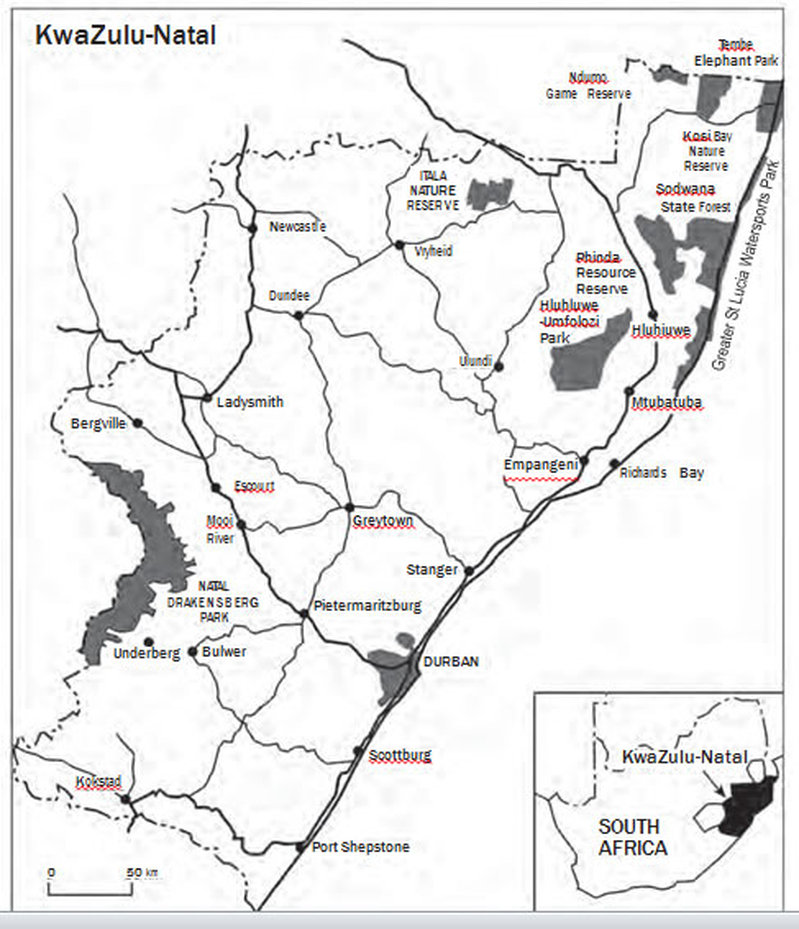

The province of KwaZulu-Natal lies on the Indian Ocean coast of South Africa and contains some of the country’s most important wildlife parks, marine reserves and wetlands. Almost 30 per cent of the coastline and just under 10 per cent of the land area falls within protected reserves, of which the Natal Drakensberg Park, the Hluhluwe-Umfolozi Park and the Greater St Lucia Watersports Park are the largest (Figure 1). Recent data suggest that over 6 million domestic tourists and over 400,000 international tourists visit the province each year to enjoy the all-year sunshine, the spectacular landscapes and, especially, the wildlife (Brennan and Allen, 2001).

The conservation of these environments is, however, compromised by the grinding poverty of many of the rural communities that live in proximity to the parks and for whom the animal and plants of the reserves represent enticing – and much-needed – resources. Poverty and conservation are seldom compatible and in the case of KwaZulu-Natal these difficulties are compounded by the legacy of the South African system of apartheid and its many injustices. In northern areas of the province, in particular, this legacy includes restricted access to land, lack of work, a general absence of welfare provision, ethnic rivalries, gender inequalities, corruption and violence. Against this unpromising background, the Natal Parks Board and its successor (since 1998) the KwaZulu-Natal Conservation Board have sought to develop conservation-based tourism and in an important change in policy that reflects new agendas in post-apartheid South Africa, with a remit to consult and involve local communities in developing sustainable management of these reserves. |

Key initiatives have included the establishment of an ambitious Community Conservation Project aimed at supporting a range of local improvement schemes – such as health and sanitation projects – and a system of tourist levies that are intended to support a fund on which communities may draw to meet the costs of local projects. Environmental education programmes (especially through neighbourhood forums) have been established in over 80 locations across the province. In this way the conservation agencies hope to persuade more local communities of the benefits of tourism and the value of conserving the protected areas as a means of attracting visitors.

Opinions on the impact of these initiatives are, however, divided. Scheyvens (2002) provides a broadly positive reading noting, for example, how controlled harvesting of resources such as reeds and wood fuel have been introduced in several parks and how communities in close proximity to entry points to parks have been able to develop small- scale tourist enterprises around the sale of craft goods. She also maps over 160 community projects and notes – as a positive development – moves to involve tribal representatives on park management boards. In contrast, Brennan and Allen (2001: 218) offer a much less optimistic view, concluding that ‘in KwaZulu-Natal, parks and other protected areas are painful reminders of apartheid’s injustices, and of the continuing privilege of whites who enjoy looking at wildlife while Africans suffer from land starvation. Community-based ecotourism has achieved little in securing the protected areas for the future, and divided rural communities have few grounds for optimism over plans of the conservation sector.’ |

Figure 1. Major conservation zones in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa

Sources

Sources

- Brennan, F. and Allen, G. (2001) ‘Community-based ecotourism, social exclusion and the changing political economy of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa’, in Harrison, D. (ed.) Tourism and the Less Developed World: Issues and Case Studies, Wallingford: CAB International., pp. 203–21.

- Scheyvens, R. (2002) Tourism for Development, Harlow: Prentice Hall.