PART IV - CASE STUDY 8.1

Las Vegas: creating a fantasy tourist city

As an urban centre, Las Vegas is unique. No other city of equivalent size occupies such an outwardly unsustainable location (within a major desert zone and physically isolated from other major urban centres) and no other city of this scale demonstrates such an intimate relationship with tourism and leisure as the ‘neon metropolis’. It is presently America’s fastest growing city that almost doubled its population in a single decade (rising from 740,000 in 1990 to 1,390,000 in 2000) and with an estimated 36 million visitors annually it is the leading destination on the North American continent and one of the top urban tourist centres in the global market. With more than 125,000 bedspaces (and nine of the ten largest hotels in the world), no other city matches Las Vegas in its tourist capacity and none rivals the truly spectacular designs that are revealed in the latest generation of resort hotels on the city’s famous ‘Strip’ (see Plate 9. 2). These hotels, in particular, have created an urban landscape that blends fantasy and pleasure within spaces and places that have taken the art of theming to new levels, producing what Rothman (2002: xi) describes as a ‘spectacle of postmodernism, a combination of space and form . . . that owes nothing to its surroundings and leaves meaning in the eye of the beholder . . . a world [that is] fantastic and unreal, yet simultaneously tangible and available for purchase’. It is the ultimate expression of the ascendancy of consumption over production – a city that ‘produces no tangible goods of any significance, yet generates billions of dollars annually in revenue’ (Rothman, 2002: xi).

The development of Las Vegas from its origins (in 1905) as a small railroad town, through its formative years as a sleazy gambling resort backed by organised crime (between 1931 and the late 1960s), to its final emergence as a fantasy city founded on corporate investment and with a global reach, has been fully described in fascinating detail elsewhere (see, inter alia: Gottdiener et al., 1999; Parker, 1999; Rothman, 2002; Douglass and Raento, 2004). The purpose of this case study is, therefore, to highlight some of the ways in which Las Vegas illustrates many of the wider intersections between urbanism and tourism that are discussed above and, in particular, the emergence of ‘fantasy’ urban spaces.

Las Vegas illustrates with great clarity the general tendency for urban tourism to focus in well-defined zones of the city, whilst leaving other areas essentially untouched. Apart from a residual area of older hotels and casinos on the fringe of the downtown (mostly around Fremont Street) the dominant tourist zone is a linear development of large-scale resort hotels and related attractions that is quite separate from the downtown area and extends for some three miles along Las Vegas Boulevard (known locally as ‘The Strip’) towards McCarran International airport. Beyond these narrow confines there are only a handful of attractions within the city limits (mostly museums, galleries and other themed attractions) that are capable of drawing significant numbers of visitors and, consequently, tourist space in Las Vegas is closely prescribed.

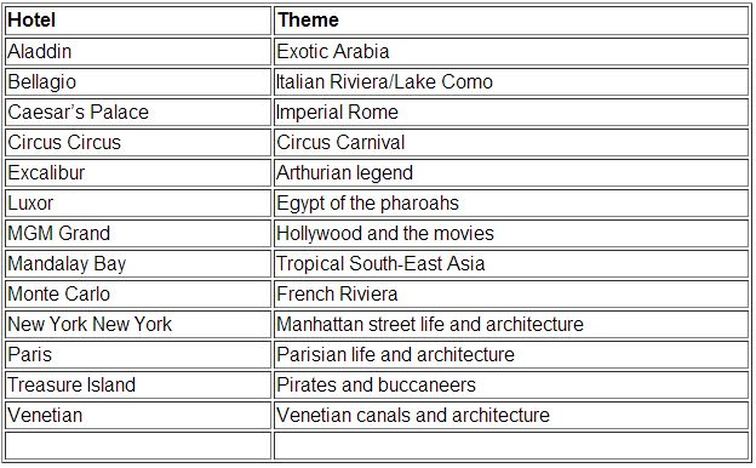

As already intimated, Las Vegas is notable for the prevalence of themed environments and the art of the spectacle. For the most part the chosen themes (which are primarily represented in the resort hotels and their interior spaces – see Table 1) are either simulations of other times and places or, more typically, simulacra, that blend time and space in impossible combinations and which depend upon staged settings and props that are, for the most part, entirely artificial. Las Vegas is a landscape of signs and signifiers but with certain notable exceptions (such as the collections of original works by artists such as Picasso that adorn the Bellagio, or the feature at the Venetian) it is a landscape without substance. But the monumental scale on which these deceptions are arranged inevitably creates a spectacular urban landscape and the spectacle of Las Vegas is arguably one of its greatest attractions.

Table 1. Themes at major Las Vegas resort hotels

Las Vegas: creating a fantasy tourist city

As an urban centre, Las Vegas is unique. No other city of equivalent size occupies such an outwardly unsustainable location (within a major desert zone and physically isolated from other major urban centres) and no other city of this scale demonstrates such an intimate relationship with tourism and leisure as the ‘neon metropolis’. It is presently America’s fastest growing city that almost doubled its population in a single decade (rising from 740,000 in 1990 to 1,390,000 in 2000) and with an estimated 36 million visitors annually it is the leading destination on the North American continent and one of the top urban tourist centres in the global market. With more than 125,000 bedspaces (and nine of the ten largest hotels in the world), no other city matches Las Vegas in its tourist capacity and none rivals the truly spectacular designs that are revealed in the latest generation of resort hotels on the city’s famous ‘Strip’ (see Plate 9. 2). These hotels, in particular, have created an urban landscape that blends fantasy and pleasure within spaces and places that have taken the art of theming to new levels, producing what Rothman (2002: xi) describes as a ‘spectacle of postmodernism, a combination of space and form . . . that owes nothing to its surroundings and leaves meaning in the eye of the beholder . . . a world [that is] fantastic and unreal, yet simultaneously tangible and available for purchase’. It is the ultimate expression of the ascendancy of consumption over production – a city that ‘produces no tangible goods of any significance, yet generates billions of dollars annually in revenue’ (Rothman, 2002: xi).

The development of Las Vegas from its origins (in 1905) as a small railroad town, through its formative years as a sleazy gambling resort backed by organised crime (between 1931 and the late 1960s), to its final emergence as a fantasy city founded on corporate investment and with a global reach, has been fully described in fascinating detail elsewhere (see, inter alia: Gottdiener et al., 1999; Parker, 1999; Rothman, 2002; Douglass and Raento, 2004). The purpose of this case study is, therefore, to highlight some of the ways in which Las Vegas illustrates many of the wider intersections between urbanism and tourism that are discussed above and, in particular, the emergence of ‘fantasy’ urban spaces.

Las Vegas illustrates with great clarity the general tendency for urban tourism to focus in well-defined zones of the city, whilst leaving other areas essentially untouched. Apart from a residual area of older hotels and casinos on the fringe of the downtown (mostly around Fremont Street) the dominant tourist zone is a linear development of large-scale resort hotels and related attractions that is quite separate from the downtown area and extends for some three miles along Las Vegas Boulevard (known locally as ‘The Strip’) towards McCarran International airport. Beyond these narrow confines there are only a handful of attractions within the city limits (mostly museums, galleries and other themed attractions) that are capable of drawing significant numbers of visitors and, consequently, tourist space in Las Vegas is closely prescribed.

As already intimated, Las Vegas is notable for the prevalence of themed environments and the art of the spectacle. For the most part the chosen themes (which are primarily represented in the resort hotels and their interior spaces – see Table 1) are either simulations of other times and places or, more typically, simulacra, that blend time and space in impossible combinations and which depend upon staged settings and props that are, for the most part, entirely artificial. Las Vegas is a landscape of signs and signifiers but with certain notable exceptions (such as the collections of original works by artists such as Picasso that adorn the Bellagio, or the feature at the Venetian) it is a landscape without substance. But the monumental scale on which these deceptions are arranged inevitably creates a spectacular urban landscape and the spectacle of Las Vegas is arguably one of its greatest attractions.

Table 1. Themes at major Las Vegas resort hotels

The most recent phases of development are also strongly illustrative of several of the new synergies between urbanism and tourism. The resort grew (and still sustains its position) on its reputation as a premier centre of gambling and entertainment, but the resort hotels have progressively refined their attractions to cater for non-gambling groups (including families), as well as recognising the appeal (and hence the value to their ‘product’) of high- quality retail environments and excellent restaurants. Elaborate, themed shopping malls and international-standard restaurants are now a feature of all the major resort hotels. According to Douglass and Raento (2004), the Caesar’s Forum mall at Caesar’s Palace now contains the world’s greatest concentration of luxury retail outlets and nearly a quarter of the country’s top-rated restaurants are located on the Strip.

Las Vegas demonstrates a remarkable capacity for reinvention and, in the process, continually asserts the fundamental importance of image. The process of reinvention is evident at both a city-scale and, more typically, within the primary components that define the tourism product. In its initial phases of development, Las Vegas quickly attracted a reputation as a tawdry and tasteless ‘sin city’, an image that would ultimately have limited the capacity for growth had the problem not been addressed. However, with the progressive development of a corporate investment culture in the 1980s, the resort has consciously reinvented itself as a destination that appeals not just to gamblers, but to a much broader base of tourists that includes families who come simply to be entertained, to shop, to eat and to enjoy the spectacle (Rothman, 2002).

Whilst the casinos (which have generally been re- branded as places for gaming – with its connotations of fun, rather than gambling – with its connotations of risk) still generate almost half of the resort revenue, the larger share comes from sectors that include retailing, entertainment and hospitality. To maintain their competitive position, therefore, the major resort hotels have become engaged on a seemingly endless process of investment and reinvestment in ever-more spectacular and lavish attractions that help to define their image: in world-class entertainment and shows, major sports events (especially boxing), theme parks rides, themed retail malls, dramatic re- enactments (including simulated sea battles), circus acts, wildlife, aquaria, IMAX cinemas and simulations of natural phenomena (such as the regular eruption of the ‘volcano’ at The Mirage).

Interestingly, although Las Vegas is an ultra-modern city that has no meaningful origin prior to 1905, the relentless drive to reinvention has also prompted some of the forms of regeneration that would not be out of place in cities with a much longer tradition. In particular, the original resort centre around Fremont Street lies on the fringes of a downtown that has become progressively more unfashionable and unattractive, as the primary resort function has migrated to the central and southern reaches of the Strip. To try to regenerate this area, a public–private partnership invested some $70 million during the mid-1990s in programmes of pedestrianisation, environmental improvement and the installation of a canopy over part of Fremont Street, onto which are projected animated images to accompanying pop music in regular, nightly, free ‘shows’. These attract reasonable numbers of interested on-lookers, but the project has done little to reverse the decline in the local casino business and the installation of the canopy effectively destroyed one of the great iconic landscapes of urban America (see: Fremont Street). The spectacle is also rather modest when compared to the glitz that typifies the latest phases of development of the Strip.

Las Vegas is a quintessential postmodern city but this quality is not simply a consequence of the depthless, representational qualities of its landmark buildings, the pastiche of styles or the collages of signs and signifiers that bombard the modern flaneurs that walk (or ride) the Strip, it also evident in the same kinds of spatial discontinuities that Davis (1990) recognises in Los Angeles. Douglass and Raento (2004) remark on the lack of any organic unity amongst the city’s components; the downtown area is a non-descript secondary zone compared to the Strip, whilst the sprawling suburbs (which, at times, have expanded at the rate of almost 50 homes a day (Gottdiener et al., 1999)) generally comprise decentred and featureless zones of housing. On the Strip itself, the major hotels function almost as micro-states – self-contained entities that compete fiercely with their neighbours to attract the tourist dollar, whilst simultaneously extending private controls over seemingly ‘public’ space. In Las Vegas, surveillance is an ever-present attribute of tourist space and on some sections of the Strip even the sidewalk (pavement) is owned by the hotels and actively policed by hotel security to ensure only appropriate activity occurs in these spaces.

However, the erosion of public space in favour of the private is just one component in a widening array of difficulties that Las Vegas exhibits. Although, as a city, Las Vegas is almost exclusively a product of the second half of the twentieth century, it appears that the urban developers have not taken too many opportunities to learn lessons from other postmodern cities, such as Los Angeles. Parker (1999) highlights issues around the low wage economy in which most workers in the city’s tourism industry are consigned; the relative deterioration of infrastructure to support local populations as the expansion of services struggles to keep pace with the physical growth of suburban Las Vegas; the lack of public amenities such as urban green space; the degradation of the natural desert environment and the excessive consumption of both energy and water by the tourist industry; and traffic congestion (and associated air pollution) of horrendous proportions. For the tourist, whose visit to the city is transient, such issues probably go undetected – masked by the ostentatious promotion of wealth and prosperity that is captured in the main tourism spaces, but the wider assessment of Las Vegas suggests that the creation of fantasy cities, perhaps inevitably, comes at a cost.

Las Vegas demonstrates a remarkable capacity for reinvention and, in the process, continually asserts the fundamental importance of image. The process of reinvention is evident at both a city-scale and, more typically, within the primary components that define the tourism product. In its initial phases of development, Las Vegas quickly attracted a reputation as a tawdry and tasteless ‘sin city’, an image that would ultimately have limited the capacity for growth had the problem not been addressed. However, with the progressive development of a corporate investment culture in the 1980s, the resort has consciously reinvented itself as a destination that appeals not just to gamblers, but to a much broader base of tourists that includes families who come simply to be entertained, to shop, to eat and to enjoy the spectacle (Rothman, 2002).

Whilst the casinos (which have generally been re- branded as places for gaming – with its connotations of fun, rather than gambling – with its connotations of risk) still generate almost half of the resort revenue, the larger share comes from sectors that include retailing, entertainment and hospitality. To maintain their competitive position, therefore, the major resort hotels have become engaged on a seemingly endless process of investment and reinvestment in ever-more spectacular and lavish attractions that help to define their image: in world-class entertainment and shows, major sports events (especially boxing), theme parks rides, themed retail malls, dramatic re- enactments (including simulated sea battles), circus acts, wildlife, aquaria, IMAX cinemas and simulations of natural phenomena (such as the regular eruption of the ‘volcano’ at The Mirage).

Interestingly, although Las Vegas is an ultra-modern city that has no meaningful origin prior to 1905, the relentless drive to reinvention has also prompted some of the forms of regeneration that would not be out of place in cities with a much longer tradition. In particular, the original resort centre around Fremont Street lies on the fringes of a downtown that has become progressively more unfashionable and unattractive, as the primary resort function has migrated to the central and southern reaches of the Strip. To try to regenerate this area, a public–private partnership invested some $70 million during the mid-1990s in programmes of pedestrianisation, environmental improvement and the installation of a canopy over part of Fremont Street, onto which are projected animated images to accompanying pop music in regular, nightly, free ‘shows’. These attract reasonable numbers of interested on-lookers, but the project has done little to reverse the decline in the local casino business and the installation of the canopy effectively destroyed one of the great iconic landscapes of urban America (see: Fremont Street). The spectacle is also rather modest when compared to the glitz that typifies the latest phases of development of the Strip.

Las Vegas is a quintessential postmodern city but this quality is not simply a consequence of the depthless, representational qualities of its landmark buildings, the pastiche of styles or the collages of signs and signifiers that bombard the modern flaneurs that walk (or ride) the Strip, it also evident in the same kinds of spatial discontinuities that Davis (1990) recognises in Los Angeles. Douglass and Raento (2004) remark on the lack of any organic unity amongst the city’s components; the downtown area is a non-descript secondary zone compared to the Strip, whilst the sprawling suburbs (which, at times, have expanded at the rate of almost 50 homes a day (Gottdiener et al., 1999)) generally comprise decentred and featureless zones of housing. On the Strip itself, the major hotels function almost as micro-states – self-contained entities that compete fiercely with their neighbours to attract the tourist dollar, whilst simultaneously extending private controls over seemingly ‘public’ space. In Las Vegas, surveillance is an ever-present attribute of tourist space and on some sections of the Strip even the sidewalk (pavement) is owned by the hotels and actively policed by hotel security to ensure only appropriate activity occurs in these spaces.

However, the erosion of public space in favour of the private is just one component in a widening array of difficulties that Las Vegas exhibits. Although, as a city, Las Vegas is almost exclusively a product of the second half of the twentieth century, it appears that the urban developers have not taken too many opportunities to learn lessons from other postmodern cities, such as Los Angeles. Parker (1999) highlights issues around the low wage economy in which most workers in the city’s tourism industry are consigned; the relative deterioration of infrastructure to support local populations as the expansion of services struggles to keep pace with the physical growth of suburban Las Vegas; the lack of public amenities such as urban green space; the degradation of the natural desert environment and the excessive consumption of both energy and water by the tourist industry; and traffic congestion (and associated air pollution) of horrendous proportions. For the tourist, whose visit to the city is transient, such issues probably go undetected – masked by the ostentatious promotion of wealth and prosperity that is captured in the main tourism spaces, but the wider assessment of Las Vegas suggests that the creation of fantasy cities, perhaps inevitably, comes at a cost.